The Living Threads of Coast Salish Wool Weaving

Wool weaving in Coast Salish territories is not just a practice. It is a way of remembering. A way of returning. Each strand carries generations of knowledge, stories, teachings and deep care.

Long before colonization, Coast Salish women wove blankets from mountain goat hair, the now-extinct woolly dog, and fibres like cedar bark. Some weavings took years to prepare and complete (Kw’umut Lelum). These pieces were not made for decoration, they were for naming ceremonies, puberty rites, marriages, funerals and moments of transformation.

In every woven piece is a quiet teaching: to listen, to feel, to honour and to carry the thread forward.

This Indigenous History Month, we honour and uplift Coast Salish wool weaving traditions through the lens and knowledge of Caitlin and Vivian—two weavers who, with resilience and artistry, carry these ancestral practices forward for future generations.

This is an interactive digital feature—learn in your own way and time. Click through each section to read the weavers’ stories, reflections and bios.

Caitlin Aleck, Te-Awk-Tenaw, from Tsleil-Waututh, began weaving in 2018. She was introduced to the craft by her Auntie Angela Paul, who invited her to a workshop and mentored her. Caitlin learned quickly, helping Angela's woven piece that was almost nine feet long.

“Our aunties and uncles and our grandparents always encouraged us. They see something in us, and they build on that,” Caitlin said.

Musqueam Band member Vivian Mearns Notaro, whose ancestral name is titə́yxʷəma:t, first learned about cedar weaving when she was a teenager. She later learned about wool weaving and joined Musqueam Weavers in 1997, a group led by Debra Sparrow and Robyn Sparrow. This group of women met each day for one year and learned all the steps of wool weaving: how to prepare the wool by splitting it, roving, (a preliminary spin prior to spinning on a spinner), spinning on a spinner to create single ply and two ply wool, and dyeing it.

“We truly call it the academics of weaving,” Vivian said. “It's not just about the pretty aesthetic piece at the end, it is about the process it takes to create a weaving.”

Every weaving holds a story—woven not just in the threads, but in the patterns, symbols, and techniques passed down through generations. For Caitlin, the meaning behind a weaving is often deeply personal and layered with teachings from aunties and other knowledge carriers. While certain symbols carry specific meanings, their interpretation ultimately lies with the weaver. “If you look at weaving, you'll find lots of different stories,” she says, “but you'll never truly know their story until they tell you.”

Weaving is also an act of cultural generosity and connection. Caitlin shares how, in the past, large weavings were created for ceremonies. Afterward, the weaving would be cut into pieces and distributed: “Each one would get a big chunk. Do you know what that represents? You are now wealthy because of this. And it’s a part of keeping us all together.”

Vivian reflects on how the Musqueam stitches and designs used today are rooted in tradition, passed down through blankets. “The stitches themselves are all done in the same way that they were done traditionally,” she explains. While colour may change, the core techniques remain true to their origins—honouring the past while weaving it into the present.

These threads carry meaning, memory, and responsibility. And in each pattern, there is more than what meets the eye—there is story, ceremony, and the strength of community.

Part of Caitlin and Vivian’s learning included uncovering the traditions of wool weaving within their own communities.

“Thousands of years ago, it was just women who did this work. Young women in the community would be watched from young ages,” Vivian said. “Who's hanging around the weavers, who's paying attention, who looks like or has the dexterity to do this work and has the passion to do the work. Then they were brought up in that role to be the weaver for the community in your family.”

Caitlin said there are few records from Tsleil-Waututh, and she relies on oral stories to understand her history.

“I really trust in this art form as a connection to my ancestors. And when you believe in something that much, and when you believe in something that hard, it comes to wrap you in love even after you're done your piece,” Caitlin said, adding she wants her work to be known for the love she pours in.

“It's ancient. And even though it looks new to you, we've been doing this since time immemorial.”

Vivian echoed that the process of weaving can be a connection to the past.

“Debra Sparrow coined the phrase, ‘Weaving through the hands of our ancestors’ and I carry that with me as I weave. I like to choose the colours that I will use in a weaving, and when I sit down at my loom, I may not have a ‘plan’ but as I start to weave, the designs come to me and the creation of the weaving comes to life.,” she said.

“We're shifting away from the colonial way of living and getting back to who truly we are. As Indigenous people, as Musqueam Coast Salish people that were able to fall back on these teachings and revive them for future generations so that it can continue to live and continue to thrive, because that's what's important.”

The impacts of colonization are deep, far-reaching and still felt today in Indigenous communities. Many traditions were taken away for generations, after cultural practices were banned by colonizers.

The traditional techniques of wool spinning and weaving, as well as the teachings that surrounded these practices, were nearly lost altogether.

“People were threatened to be put in jail for weaving or speaking the language, dancing, using masks, our traditional way of life,” Vivian shared, adding that there was a period of about 85 years when weaving practices stopped entirely. “Many aspects of our culture went ‘underground,’ and in the early 80’s when weaving was being revived, many members were excited to learn and create weavings.”

Caitlin knows her family has connections to weaving, but they were impacted by residential school.

“I know that my grandma was a cedar weaver because we have her baskets,” she said. “I know that they had the skills to do these things. But with residential school, it was taken. Everything was taken from them. Everything was stripped away from them.”

Through resistance, resilience and the support of those who still held the knowledge of these traditions, Coast Salish weaving began to see a revival in the 1980s.

“My generation, we're able to revitalize it in such a good way that now we're going back two, three, four generations to make them proud. Language. Culture. Weaving. Carving. Beading. Connection. Community. Family. It's all coming back. And I think that's really significant. And it's really something beautiful that people need to open their eyes to if they haven't already."

Even the number of weavers has increased significantly. In Musqueam, there are at least 50 to 60 weavers today. In the 1980s, there were only a handful of people.

“It's really exciting to see how much the community and members want to learn and how they want to take it on their own, and to watch them evolve,” Vivian shared, and said she hopes her own work is recognized as being part of this revival.

“We are here. We're still here. We've always been here. We never crossed the land bridge. We didn't fall from the sky.”

For Caitlin and Vivian, Indigenous History Month is a time to celebrate and recognize First Nations communities that have been on this land for thousands of years. It’s a time to listen, break down stereotypes, ask questions and honour culture.

“Indigenous History Month to me is really important in that it puts it puts a face to the name of our people ... you may not have met anybody in that culture, but when you can break down stereotypes and you can educate and share information, knowledge is power,” Vivian shared.

“There's nothing holding us back. We have no prohibitions. We have nothing that's saying we're ‘not allowed to’ anymore. People are more open and willing to listen and learn.”

One thing is certain: these practices of listening, learning and celebrating cannot end on June 30.

“Indigenous people celebrate our culture 365 days a year,” Caitlin said. “I think there's so much to learn and know and to grow that one month is just not enough.”

Caitlin Aleck, Te-Awk-Tenaw, is a səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh Nation) artist specializing in weaving and digital arts. Wool weaving awoke in Caitlin in 2018, and she now creates art for ceremony, teaching, and reconciliation. With cedar weaving lineage passed down through her grandfather’s side from Xwchíyò:m, and wool weaving passed down through her grandmother’s side, she has a strong connection to the artform on both sides of her family. Her thoughtful and passion-driven work is heartfully tuned, with a strong focus around culture, history, and ancestral connection to the land. After weaving for 7 years, she has an understanding that weaving can be translated from story into design elements. Transforming these elements on a public art scale is her way of sharing her ancestral knowledge for generations to come.

Caitlin Aleck

səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh Nation)

“Indigenous people celebrate our culture 365 days a year. I think there's so much to learn and know and to grow that one month is just not enough.”

What would you like your work to be known for?

What a good question, right? My family always instilled in me that we should meet people where they're at. And working with people in their art practice means helping them in any instance that you can. And I think with that mentality is what I'd want my weavings to be remembered for. It's about covering my family and covering the ones that I love in my weaving, because that's the heart of it. It’s a power thing to cover people in something you made, something the ancestors helped you make and the love shown will be kept forever.

What does Indigenous History Month mean to you, and how do you hope people engage with it?

I think about togetherness. I think about honouring those. And everyone around us, when it comes to Indigenous Peoples Month, I think it should be a celebration, and I think it should be a reflection to where we were to where we're going and celebrating along the way.

Where can people see or support your work?

You can find me on Instagram—I'm working on getting better at sharing updates there!

Visit Caitlin Aleck's Instagram page

Vivian Mearns Notaro

xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam Nation)

“We have always been on this land and we will continue to be here for future generations.”

What would you like your work to be known for?

As a Musqueam weaver of wool and cedar bark, I want my work to be known to support the revival of weaving in my community of Musqueam. A revival of our weaving techniques and practices that were left by our ancestors who have gone before us. To be able to assist new and upcoming weavers to allow our teachings to be handed down to the younger generations.

To teach younger people, so that they can say, they learned when they were little and they learned at home!

How does your weaving keep your culture strong and alive?

My weaving contributes to the survival of our cultural practices and that ensures that it lives on for future generations. It makes us stronger as a community, we come together and learn from each other, learn from the blankets in the museums and that connects us to our past as we move to the future.

I am excited that so many members want to learn and that makes it stronger too.

Where can people see or support your work?

I don't have a website. Generally, most of the work I do is by commission. I have people that will reach out and know that I'm a weaver, or say, so people will come and ask for different items, baskets, sometimes headbands, you know, truly, truly by word of mouth.

Contact Vivian via email | Vivian's TikTok page

Vivian Mearns Notaro, titə́yxʷəma:t, is a Lands Registry Officer and Lands Assistant at Musqueam Indian Band, and a skilled weaver of cedar bark and wool. Deeply rooted in cultural traditions, she also shares her knowledge as a Cultural Educator, helping others connect with Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

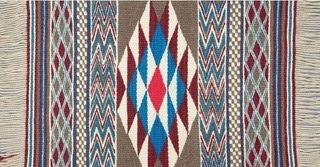

Disclaimer: The artwork featured in this post is protected by copyright laws. Any reproduction, distribution, or use of these images without the explicit permission of the artists is strictly prohibited and constitutes a violation of copyright. Please respect the intellectual and cultural property of the creators.